2012-01-01

Abstract

2011 was filled with plenty of security stories involving spam, malware, hacking and more. Terry Zink picks out his top ten newsmakers.

Copyright © 2012 Virus Bulletin

2011 was filled with plenty of security stories. It wasn’t just spam that made the news, but spam, malware, hacking and more. (When I use the term ‘spammers’ in this article, I use it in a generic sense to refer to people who spam, distribute malware, perform black search engine optimization, etc.). It was a jam-packed year, so let’s take a look at the biggest newsmakers. (Please note that the views and opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not necessarily state or reflect those of Microsoft.)

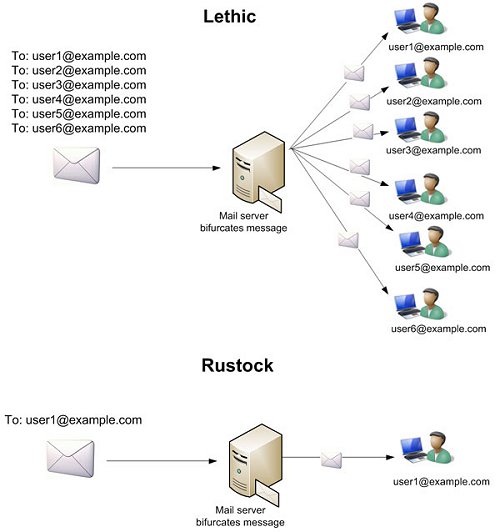

For several years, the spamming botnet with the biggest footprint was Rustock. Its characteristics were to ‘wake up’ at a specific time each time day, send hundreds of thousands of spam messages, and go back to sleep. Furthermore, Rustock sent lots of messages to lots of different email users from a lot of IP addresses. In other words, its footprint was a mile wide and an inch deep. This distinguished it from some other botnets like Lethic that send a lot of email in one Internet connection (that is, an email with lots of recipients vs Rustock that sends to one recipient per email):

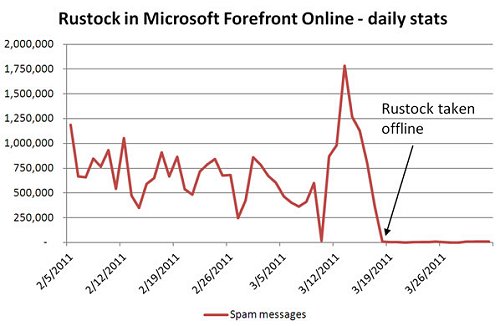

But on 16 March 2011, working with Microsoft, Shadowserver and some other partners, the US Department of Justice obtained a court order to seize command-and-control servers that were responsible for running the Rustock botnet in the United States. Virtually overnight, spam from Rustock plummeted and has never recovered:

It was a great takedown, federal authorities walked into server rooms and confiscated actual hard drives from command-and-control servers (a warrant was obtained and the action was coordinated across a couple of US states).

Microsoft had to make an effort to serve the operator of the botnet in court and give him a chance to explain himself. Unsurprisingly, he never showed up.

For years, we have heard about the scourge of spam:

Spam volumes way up!

95% of all email is spam!

Spam volumes continue to increase!

The trend was so bad for so long that everyone began to wonder whether spam would eventually become 99% of email, and then 100% (rounded up). The amount of processing resources it would take up would threaten to ruin email (which is why other technologies like RSS, instant messaging, and social networks always promise to replace email… but never do).

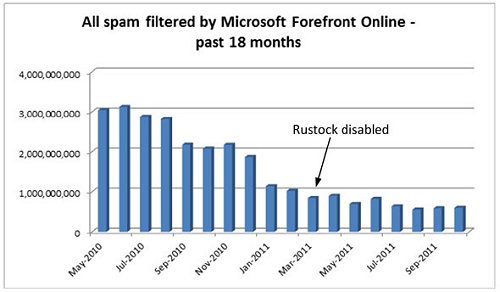

But, starting in late 2010 and continuing throughout 2011, spam levels started to decline. And they didn’t just decline a little, they declined a lot.

What caused this steep decline? The answer is that nobody knows for certain, although there are theories:

In late 2010, spam affiliate network SpamIt (also known as GlavMed) shut down and some of the revenue streams for spammers disappeared.

In March 2011 the Rustock botnet was disabled. However, while this was significant, the decline in spam had already begun before the Rustock takedown.

In response to botnet takedowns, spammers have adjusted their strategy – rather than sending a lot of email to a lot of users, they are keeping their botnets smaller and creating more direct spam campaigns.

Pavel Vrublesky, the founder of Chronopay, which is allegedly responsible for online spammer payments, was arrested (on non-spam-related charges). Payment processing for spammers faced a new bottleneck.

Spam from botnets still dominates the spam waves, but ‘grey mail’ spam – pseudo-legitimate bulk mail campaigns – have arisen and are more difficult to stop.

The battle against spam isn’t over, it has just shifted from one form to another. Now the problem of spam isn’t that it gets through because there’s so much of it that filters can’t keep up, but that filters can’t keep up because its smaller numbers are more difficult to detect.

In March, some disturbing information leaked out of RSA, the company that has long been associated with security. These are the guys that make the key fobs that many of us use to get onto our corporate networks using two-factor authentication.

Somebody, somewhere, sent an email to an RSA employee – not a high-level employee, just a regular ham-and-egger like you and me. The email came with an attachment. The subject line read something like ‘2011 Recruitment Plan’. It went into the employee’s junk mail folder.

The employee opened their junk folder, dug the email out, opened the attached Excel file, and their computer became infected with a piece of malware when it exploited a previously undocumented Flash vulnerability. The intruders were now inside the company’s systems.

It is unclear what the intruders were able to access because RSA representatives haven’t exactly been forthcoming with a full list of what was compromised and what wasn’t (not that I can blame them). But what we think we know is that it was a very sophisticated hack, and the hackers accessed the algorithm that RSA uses on its key fobs, as well as the seeds for the encryption algorithm.

RSA offered to replace the fobs of its customers and then issued the standard set of advice: use strong passwords, control access to the production environment, and re-educate employees about opening email messages with suspicious attachments.

RSA wasn’t the only big-name corporation to be hacked using a sophisticated attack this year. Large government contractors like Lockheed Martin and Seagate Technology were also hit, as well as the US Internal Revenue Service and Freddie Mac.

Who was behind all of these attacks? Well, that’s the subject of the next big story of 2011.

In September 2011, McAfee released a report, in conjunction with Vanity Fair magazine [1], about Operation ShadyRAT.

In the report, McAfee studied several cyber intrusions where numerous victims had been targeted – government agencies in the United States, Taiwan, South Korea, Canada; large corporations in a number of countries; and non-profits such as the International Olympic Committee.

Why were these entities targeted?

There wasn’t a clear financial motive behind the attacks, no economic gain. Generally, if a cybercriminal hijacks your computer, he either wants your usernames and passwords so he can steal money from your back account, or he wants control of your computer to use it as part of a botnet.

Who was behind the attacks? McAfee wouldn’t point a finger at any particular culprit, the researchers just presented the evidence and then let the policy makers draw their own conclusions. However, at least one security expert believes the identity of the culprits is obvious: ‘All the signs point to China,’ says James A. Lewis, director and senior fellow of the Technology and Public Policy Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, adding, ‘Who else spies on Taiwan?’

Regardless of who is behind the attacks, 2011 saw a huge increase in the detection of APTs – Advanced Persistent Threats. An APT is a hacking attack that is advanced because it contains sophistry that is beyond the abilities of most hackers. It is persistent because it occurs over and over again. APTs are usually attributed to other countries – first, because states are the only entities that have the resources to continually fund these types of threats, looking for vulnerabilities in software. Second, because the motive for APTs is unclear and looks more like espionage, and it is assumed that states have more use for it than private enterprise.

What Operation ShadyRAT exposed was the size and scope of this type of activity. And while it is fun to accuse China of being behind all these hack attacks, the fact is that there are many countries that all have varying degrees of skill when it comes to collecting intelligence. And that’s what APTs are all about – espionage. The United States, China, and Russia are all very good at collecting intelligence. They have well-funded government departments dedicated to acquisition of information. Other countries – such as Ireland or New Zealand – do not have so many dedicated resources.

The arms race has been going on for years. What changed in 2011 was that we became very much more aware of what is going on.

Maybe we liked it better when we didn’t know so much.

Hacking isn’t all fun and games, as illustrated by my previous two stories. But this next story kind of is fun and games. Unless you were one of the targets, that is.

Anonymous is an international hacking group, spread through the Internet, initiating active civil disobedience while attempting to maintain anonymity. CNN has referred to the group as one of the successors to WikiLeaks.

In April, Sony revealed that it had been the victim of a hack where a raft of user information was stolen from its servers and posted online. Anonymous had previously announced that it had planned to do this in response to Sony’s lawsuit against George Hotz (a young hacker who had hacked into the PlayStation). Further attacks were carried out against the Spanish Police (DDoS), websites of the Malaysian government, and against the Orlando Chamber of Commerce.

In June, a suspected splinter group of Anonymous – LulzSec – launched its own hacking attacks. The group went after the websites of the CIA, Sony, Fox News, PBS and others. During the summer, it seemed like there was a new hack attack each week and what became newsworthy was not the fact that a company had been hacked, but that a week had gone by without an attack.

The hack attacks of LulzSec and Anonymous eventually quietened down. In contrast to the APTs that continue to occur to this day, LulzSec and Anonymous eventually wound down their campaigns (perhaps in response to generating too much heat, or perhaps in response to law enforcement catching up with some of the members of their group). But also unlike the APTs, these hacking incidents were very public. Both groups claimed responsibility for their break-ins and revelled in the attention they received.

The motives of these two attacks are very different from the APTs; whereas states desire the acquisition of information, Anonymous and LulzSec are driven by hacktivism. Their motives are political in nature and are designed to poke fun at public figures with whom they disagree. Sony acting as a bully by infringing on users’ ‘rights’ to hack the PlayStation? Or the Arizona state government building a fence to keep out illegal immigrants? What better way to protest than breaking into their computer networks!

Not all of the hacks were politically motivated, though. By their own admission, some of the groups’ activities were carried out through sheer bravado.

The problem with bravado is that if you generate too much publicity, eventually the law catches up with you. In stock trading, there’s an old saying: ‘There are old traders, and there are bold traders, but there are no old, bold traders.’

LulzSec and Anonymous would do well to take heed of that.

For years, Microsoft has devoted resources to stamping out the problem of malware that infects its operating systems. Fair or not, Windows has earned the reputation of being insecure and susceptible to malware. In contrast, Apple has historically prided itself on the belief that it is not prone to malware. Television commercials have even been released implying exactly that.

But this year, something odd happened – malware started to appear for the Mac. And users were falling for it.

It’s not that malware has never existed for the Mac; it has. It’s just that this year it became really obvious that malware exists for the Mac because of its prevalence. Reuters announced [2] in May that McAfee had seen a steady stream of malware related to the Mac, and users called in asking for assistance on how to get rid of it. At first Apple denied that this was a problem [3]. For a company that is as image-conscious as Apple, I can see how it might be in denial that its computer wasn’t as perfect as it thought it was. Eventually, the company released software that removed that malware and included it as an update to MacOS.

More malware variants did not keep popping up, leading some to think that this was just a temporary phenomenon. Those of us in the PC industry don’t agree, though. In fact, some of us experienced just a little bit (i.e. a lot) of schadenfreude at this turn of events. Not because we’re happy that the Mac has got malware, only that outspoken Mac users were put in their place just a little bit (I’m having fun with Mac owners, but that’s okay because I am one, too).

The good news in all of this is that Apple responded to the problem fairly quickly and is now starting to get into the rhythm of security releases. Like anything, once you become popular, you become a target for online criminals.

And that brings me to the next story.

The post-PC era. That’s the new buzzword these days. Personal computers are getting smaller and smaller. First we had huge machines with vacuum tubes. Then we invented transistors and the machines became smaller so that they could fit on a desk. Then they fitted onto our laps. Now, they fit into our hands.

Remember when a phone was just a phone? You used it to call your friends. Then they started doing things like browsing the web and playing music. Now they do a whole lot more, and you can almost put your entire life on your smartphone (of course, there’s so much more to life than playing Angry Birds – but I digress).

And that’s just it. Our phones are now doing more and more, which is why we call them ‘smartphones’. They are like miniature computers that we carry around with us, but, like yesterday’s computers, they are prone to the same type of problem – malware.

Mobile malware is still in its infancy and hasn’t yet taken off fully, but it is growing. And just as the PC became a target for malware writers because of its ubiquity and open systems (anyone could write applications), smartphones are becoming targets for malware writers where the systems are ubiquitous and the platform is open. And the fastest growing target is Google’s Android.

There are two main types of malware for Android:

SMS trojans that send background messages over your phone once it is infected.

Data theft trojans that steal your personal information and send it back to a remote server.

Does this mean that smartphones, particularly ones that run Android, are especially vulnerable? Not exactly. The smartphone space is still fairly new, and luckily, that still works in its favour. As long as you buy or install applications from reputable places, you are not going to have much of a problem (most of the time). Unlike the iPhone, Android doesn’t have a central clearing house for apps and users are fooled into thinking that everything is secure, when it really isn’t. Thus, while Android’s openness is its strength, it is also its weakness. This is exactly like Windows. But the prevention is also exactly the same as for Windows – make sure you buy or install applications from reputable places.

There really is nothing new under the sun. And speaking of nothing new, that leads me to my next story.

Twice per year, Microsoft releases its Security Intelligence Report [4]. Each time it releases one, it writes about a particular theme and the latest one, SIR volume 11, released in October, looked at zero-day malware.

In the security industry, zero-day malware gets a lot of hype. Users are afraid of it – they fear that one day they will be hit by a virus infection that will spread through their computer and erase all of their files or infect their computer and steal all of their data. Worse yet is that they can have all of the possible security solutions in place, but nothing will protect them because there are no anti-malware signatures for zero-days. There is no defence!

Microsoft decided to examine the threat of zero-days and assess whether the fears were justified, and to put this type of threat into context relative to all of the other threats that are out there.

The analysis revealed that zero-day threats account for far fewer than 1% of all malware threats out there. The fact is that for all of the hype that exists, for the vast majority of threats there are defences already in place. You can protect yourself if you just follow basic steps like keeping your software up to date, running a firewall, and running anti-virus software.

The report was not intended to play down the risks posed by zero-day malware or to encourage IT administrators to relax and let down their guard. Instead, the message is that we all have a limited set of resources and need to prioritize the tasks we do and where we allocate those resources. Having the right information lets us keep our priorities straight. Users are the most vulnerable part of any security system, so maybe resources are better spent educating users, implementing secure practices and following basic security steps. Many of these practices are pretty easy to implement. You can action them today.

And that’s the point of the report.

My favourite story of the year is this one. Why? Because it offers a genuinely new method of fighting online crime.

For years, the anti-spam and anti-malware industry has focused on technical solutions to the problem of online abuse. Most of the top stories of 2011 are about that. Heck, it makes sense; we have to use the tools we have available, and technical solutions are how we solve technical problems.

These solutions are augmented with user education (teaching users not to fall for scams) and criminal prosecution of online criminals. The former recognizes that scams are a human problem, and so does the latter.

Where the University of California (UC) offers a unique insight is in looking at the motivation of criminals – for the money. What if instead of going after the criminals, we dried up their money supply? The security industry insists that if people stopped buying the stuff spammers are peddling, eventually they would go out of business (the same as any other enterprise). But if people won’t stop buying the stuff, then maybe we can cut off the criminals’ supply of money.

The University of California started buying from spam campaigns and then looked at the credit card transactions. Most people are only vaguely aware of how this process works. You go to a website, enter your credit card details, and like magic you receive your goods a few days or weeks later. You then happily pay your credit card bill where said transaction ends up on the statement.

What really happens when you initiate a credit card transaction is that the big companies like Visa or MasterCard act as a clearing house. The financial transactions really go through the banks. They are the ones that authorize or clear these transactions, and they are the ones with the authority to approve, or more importantly block these transactions. The UC researchers discovered that the majority of credit card payments for spammy products went through three banks – one in Azerbaijan, one in Latvia, and one in St. Kitts and Nevis. The banks are a major bottleneck in getting money to scammers.

Instead of going after users or using technology to keep users safer, the researchers proposed pressuring banks to clamp down on fraudulent banking transactions. After all, if three banks are responsible for three quarters of spam payments, then shutting those down would represent a real disruption to the spam business.

Moving the online abuse infrastructure is relatively easy. It’s not difficult to register domains or set up botnets. However, it is time consuming and costly to negotiate payments with banks. Spammers cannot simply pick up and move banks the way they can with domains. It is a human process that has checks and balances.

And that is why this is my favourite story. I had never thought of this before. If automation is the key to spamming, then making spammers go through manual steps is a great way to disrupt their cash flow patterns.

Maybe there’s hope yet for solving the abuse problem.

One of the biggest geopolitical stories this year was the Arab Spring where popular uprisings led to changes in leadership in Tunisia and Egypt. Since that time, there has been debate as to the role that social media played in the toppling of the governments.

At the time, it certainly looked like Facebook and Twitter played a significant role since they were major organizing tools for the demonstrators. By creating user groups, fan pages and trending topics, and then using them to organize planned demonstrations, protesters created a decentralized movement that eventually forced change. I recall one article where an interviewee said ‘Thank you, Mark Zuckerberg!’. The government of Egypt cut off Internet access for a period of time, but one study [5] by the University of Washington concluded that this only increased support for the movement. After all, an oppressive regime that suppresses freedom of expression deserves removal. This only fanned the flames of revolution.

The point was driven home: we live in a new age where the Internet and social networks have the power to topple oppressive regimes.

The problem is that the role of Facebook and Twitter was not as pronounced as some of us think. Numerous blog writers and editorials claim that Facebook’s role in the Arab Spring was overstated. Even Facebook’s VP for Advertising and Operations commented, saying ‘When you see what is happening, you understand why changes are happening within the social media. However, I think Facebook gets too much credit for these things.’ [6]

Behind the scenes, there were other political forces at work. In both Tunisia and Egypt, the military forced the respective presidents to step down because they either disapproved of their policies (in the case of Tunisia) or of their succession plans (in the case of Egypt). As evidenced by other protests across the region in other countries, protests do not always lead to regime change. Make no mistake, social networks give visibility to social movements, but real action requires the strength of the military.

Thus, while Facebook did have a small role to play in the Arab Spring, it had a lot of help from the traditional arbiters of power.

Yes, I said that these were the top ten stories of 2011, and here I am at number 11. Consider this a bonus story.

In November, the FBI announced the arrest of six Estonian nationals in what some call the biggest cyber-heist arrest in history. Responsible for the DNSChanger malware, which redirected unsuspecting users to rogue Internet pages, the botnet that the suspects operated consisted of over four million computers.

As with Rustock, the rogue command-and-control servers were seized and infected requests to DNS servers were replaced with legitimate ones.

Not a bad Christmas present for law enforcement.

Well, that’s the way I saw 2011. From APTs to hacking to malware and spam, there was a little something for everyone. I’ve now written a couple of these ‘Top Ten’ articles [7], [8], and while there is a lot of overlap, I’m always surprised by the new stories that appear and make the list.

Who knows what stories will make it onto my 2012 list.